The Chilling History of Ice

We use it at tailgating, backyard barbeque parties, and even cross-country road trips. Did you ever stop and wonder, though, where did ice come from?

For the bulk of human history, man has been preserving food using the elements provided by nature. Ice, a common ingredient used in many of those conservation techniques, was also a means to make drinks cooler. In this article, let’s explore the journey of this refreshing product, from being a rare treat for only the wealthy in ancient civilizations to making its way to every household in the United States.

Early Techniques: how ancient humans froze or made ice

Food preservation finds its roots way back around 1000 BC when the Chinese civilization figured out a way to cut ice that was formed on top of the cold streams or snow into blocks and use it as a means of preserving food.

Around 500 BC, the Egyptian and Indian cultures had discovered rapid evaporation as a means to cool water placed in clay pots, on straw beds. Evaporation, combined with the decrease in night temperatures, froze the water.

Ice would form on cold nights by setting out shallow earthenware pots filled with water

By 400 BC, the Persian society had become proficient in the art of storing ice during peak summer in an underground area of the desert. Their engineers developed an evaporative cooler structure called Yakhchāl (Persian for “ice pit”), which was a dome-shaped building up to two stories tall, with an equal amount of space underground. The underground area kept ice, as well as any other food, cool through the use of air flow. Its wall was made out of a special mortar called Sārooj – composed of sand, clay, egg whites, lime, goat hair, and ash in specific proportions – which was resistant to heat transfer and completely water resistant.

Exterior and interior (dome) of the Yakhchal in Meybod, Iran

As far back as the 5th century BC, the ancient Greeks were known to refresh themselves with snow, flavored with honey or nectar. Alexander the Great built the first Greek icehouse and often enjoyed eating frozen milk with honey accompanied by various fruits and wine. Their neighbors, the Romans, also had ice and snow mixed with their juices and wines to cool themselves. Legend has it that Emperor Nero usually had snow transported by runners from the mountains to Rome for these purposes.

Wealthy Romans were known to have snow carted down from the mountains to grace their table

Progression to the Old West: how ice became a commodity in America

Modeled after European-style large deep storage pits, early cold storage systems in America were located underground in the 17th-century. According to the Project Gutenberg eBook, there may have been a hut built over the pit to trap cold air and help preserve perishable items like meat, packed in ice and straw for insulation. Pond ice was usually cut and stored in the pit in late winter. Sometimes it lasted until late summer or early autumn.

Archeological excavations revealed that icehouses were built in Jamestown over 300 years ago

Painting by Sidney E. King

In 1802, Maryland based farmer and inventor, Thomas Moore, created an “Ice Box”. Initially named the “Refrigeratory”, this was an oval tub and lid made from cedar wood. The rectangular tin box, as seen in the sketch below, allowed space for ice between it and the wood. Both were covered with cloth and rabbit skin.

He developed it to transport butter from his home in Montgomery County to Georgetown, 20 miles south at night. Due to his new invention, the night travel was not necessary anymore. The butter stayed firm and sold for 4d to 5 1/2d per pound higher than other competitors, thus paying for the box after four trips. He later coined the word “Refrigerator” to describe the appliance he patented in 1803, whose fan included President Thomas Jefferson.

Sketch of the “Refrigeratory”

A couple of years later, circa 1820, an American businessman and merchant named Frederic Tudor – who eventually earned the nickname “Ice King of the World” – devised a brilliant way to insulate ice aboard ships by packing it in sawdust and established a national supply chain, distributing it as a commodity from New England to the hotter parts of the country (and the world eventually).

“Ice King” Frederic Tudor | Photo Credit © Wikipedia

Frederic Tudor not only introduced the world to cold beverages on hot summer days, he generated solid demand for ice among Americans that never existed before. When his brother, William, teased that they should harvest ice from their estate’s pond and sell it the colonists sweating in the West Indies, Frederic took the notion seriously.

His journey took over 10 years, and started by him first dropping out of Harvard, and then creating a market by convincing people they needed his product. He travelled across United States getting people to try out ice, and sometimes even giving it away for free. He wholeheartedly believed he could change the way people drink and even taught people how to make ice last, and what to do with it.

Breaking the pond ice | Photo Credit © Getty Images

To get started in the business of exporting ice, Tudor took on a lot of risks which were unusual at the time. No one believed the idea would work. In fact, no ship in Boston would agree to transport the unusual cargo, so Frederic spent nearly $5,000 to purchase his own ship. Incurring a lot of debt, he was even imprisoned for his early business troubles, but he persevered through this to ultimately build a highly successful ice business empire.

Ice Harvesting | Photo Credit © Getty Images

Initially, only one-tenth of the harvested ice could be sold. What’s worse, the whole operation was incredibly unsafe and dangerous due to usage of sharp instruments and chilly waters resulting in numb hands. The 300-pound blocks of ice could slide easily, knocking down men and breaking their knees.

Soon came a savior – Nathaniel Wyeth – an innovator who became Tudor’s right-hand man in 1826, invented a much faster and safer harvesting method using a horse-drawn plow to cut the ice into large grids. Laborers sawed the blocks apart and plunked them into canals to float them downstream. Wyeth also put an assembly process where conveyor belts would grab the grid, hoist it into icehouses, and could remain there, stacked 80 feet high, for the rest of the year.

By 1830s, Tudor’s customers included Queen Victoria as well as the British colonists in India. Tudor’s ice was shipped from Boston to far off places including Rio de Janeiro, Sydney, Bombay, as well as other Caribbean islands. While back at home, nearly 52,000 tons of ice traveled by ship or train to 28 cities across the United States including Charleston, South Carolina, Savannah, Georgia and New Orleans.

The cool rush was on! Tudor’s big idea ended up altering the course of history, making it possible not only to serve cool mint juleps in the dead of summer, but to dramatically extend the shelf life and reach of food. Suddenly American society could eat perishable fruits, vegetables, and meat produced far from their homes. Ice built a new kind of infrastructure that would in time become the cold foundation for the entire modern food industry. By the late 1880s, ice was the second largest export in the United States, right behind cotton.

The birth of mechanical ice: how ice was produced artificially

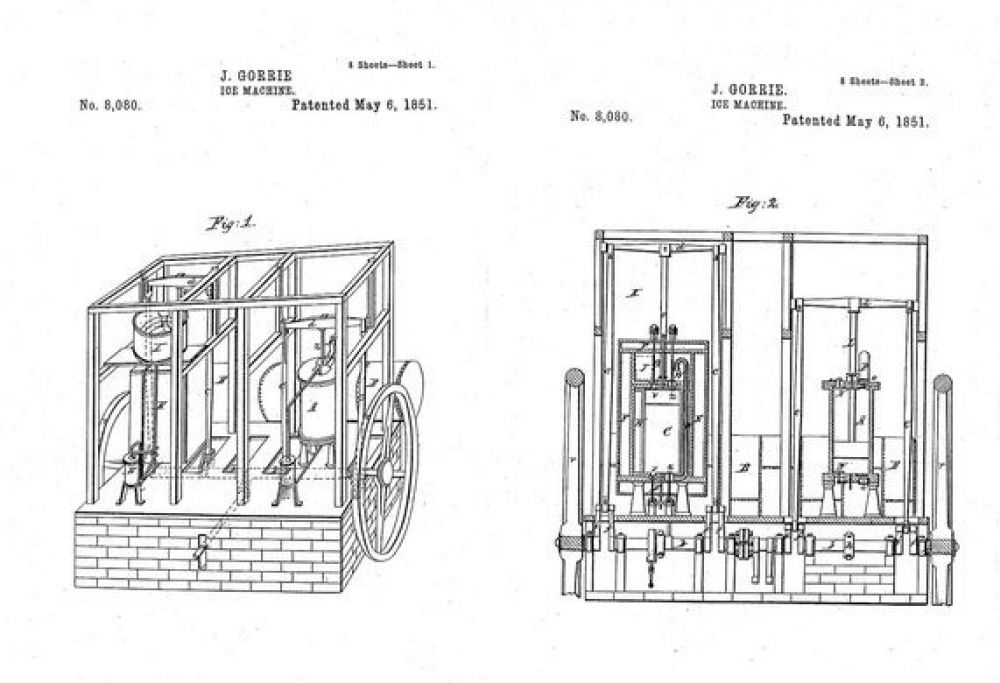

In 1847, Dr. John Gorrie, a physician scientist and humanitarian based in muggy port town of Apalachicola, Florida, sought to improve the survival rate of his malaria and yellow fever patients by cooling them down. He suspended pans of cold-water high in their sickrooms, so the cooled, heavy air would flow downward. But ice was expensive to purchase in Florida during summer, so he was motivated to build a machine that made it mechanically. Moreover, there were growing concerns over the quality and safety of the natural ice pulled from lakes and rivers. He spent more than five years experimenting, and had a prototype built in Ohio by the Cincinnati Iron Works.

Dr. John Gorrie, the father of refrigeration and air conditioning

Even though he received a patent for his mechanical refrigeration machine in 1851, no one took his idea seriously and he eventually failed at business. His business partner died, and he was not able to fund the idea. Moreover, Gorrie’s inefficient, leaky machines were mocked in the press by the ice-shipping establishment. He died in poverty and ill health in 1855, still in his early 50s while his ice maker concept sat on the shelf for several decades.

Gorrie’s patented ice machine in 1851 | U.S. Patent No. 8080

In 1853, Alexander Twining was awarded U.S. Patent for developing the first commercial refrigeration system to artificially produce ice. Around the same time, James Harrison from Australia successfully built a refrigeration machine capable of producing 3,000 kilograms of ice per day and in 1855 he received an icemaker patent in Australia.

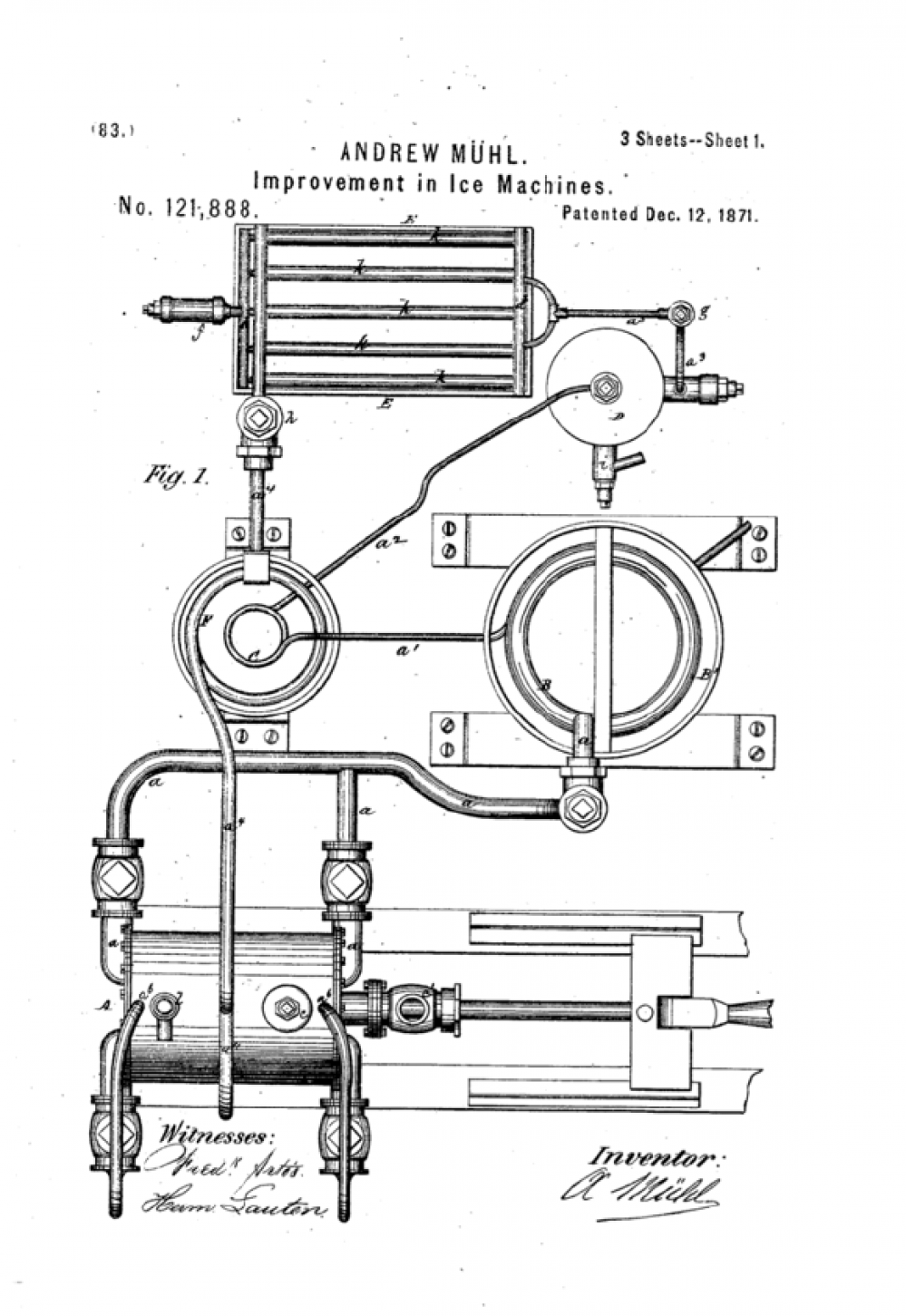

To help service the expanding beef industry, Andrew Muhl built an ice-making machine in San Antonio, Texas. In 1873, the patent for his invention was contracted by the Columbus Iron Works, which produced the world’s first commercial icemakers.

Muhl’s patented Icemaker in 1873 | U.S. Patent No. 121888A

As the end of the century approached, keeping things cold became all the rage in the food and beverage industry. In 1917, the National Association of Ice Industries was formed with over 1,000 ice companies operating either pulling block ice from the northern lakes and rivers or in the early stages of mechanically produced block ice.

In 1938, Henry Vogt built the first commercial automatic sized ice-machine, the Tube-Ice Machine. Prior to this, ice was always produced in the form of block ice. Vogt’s groundbreaking machine would freeze ice automatically in vertical tubes, momentarily thaw ice from the tubes, and then cut it into short cylinders with a hole in the center (as a result of the falling film of water freezing inside the vertical tubes).

In 1968, Charlie Lamka, an ice company operator from Amarillo, TX, invented and marketed a volumetric packaging machine that revolutionized the industry switching from ice packed in cumbersome paper bags to slick and colorful plastic (poly) bags. Plastic bags increased production significantly and were much easier to store and deliver to various retail stores.

Meanwhile, the National Association of Ice Industries changed its name to the National Ice Association in 1958 and then the Packaged Ice Association in 1971 to reflect the primary product of that time period, packaged ice, which has since then been sold in 2 forms – ice blocks and ice cubes. They rebranded themselves again in 1998 to the International Packaged Ice Association (IPIA) to represent the producers and suppliers across the globe. Today, the IPIA represents over 400 ice producers and distributors worldwide, that recognize that Ice is a Food and is missioned to provide the retailers and consumers with a safe, high-quality, consumable food product!

Conclusion

From an industry that was once based on animal power and harvesting ice from nature, to one based on innovative, food grade quality manufacturing methods and distribution logistics, packaged ice has come a long way. The next time you put your lips to a smoothie, an iced tea, a strawberry daiquiri, a mojito, or a chilled beer, take a moment to thank Frederic Tudor, Dr. John Gorrie, and Alexander Twining who had the vision in their time to turn packaged ice into an indispensable commodity.